THAT’S GREAT! A life lesson taught to me by Allen Ginsberg.

Yitgadal v’yitkadash sh’mei raba b’alma di v’ra chir’utei.

That’s the first line of the Mourner’s Kaddish transliterated from Hebrew. Kaddish is chanted to mourn the very recent passing of close relatives and then on every anniversary of the relative’s death. You’re not supposed to recite Kaddish for the passing of friends, favorite rock stars, celebrities, thoroughbreds, and beloved sports figures, so I usually don’t. As a friend of mine is fond of saying, “This death shit is really beginning to piss me off!”

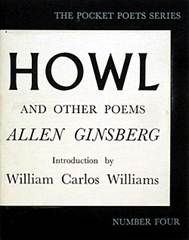

One day in mid-May 2025 I drove down from Westport to Kew Gardens listening to Howl and Other Poems by Allen Ginsberg, a recording made in 1959 and released on Fantasy Records. When I think of Allen Ginsberg, who died on April 5, 1997, I think of my middle brother, Lenny, who died on November 24, 2004.

When Lenny and I were teenagers in the mid-1960s, and among our group of friends, Lenny was one of the two intellectuals in our group. The other was not me. What constituted an intellectual to a bunch of mid-1960s working class Queens teen males? Cynicism, argumentation (Lenny was an excellent debater and later, an equally combative attorney), a simultaneous blend of awareness, questioning, and rejection of authority (see Marx Brothers here), wide-ranging knowledge, and putting in the actual intellectual work by reading texts to determine their value and meaning. Online summaries and Copilot were far away in the future.

V’yamlich malchutei b’hayeichon u-v’yomeichon, uv’hayei d’chol beit yisrael, ba-agala u-vi-z’man kariv, v’imru amen.

Lenny read L. Ron Hubbard’s Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health at 15 or 16 and intellectually ripped L. Ron a new one before us, all while explaining the faults in Hubbard’s reasoning. That influenced me in how I looked at all other types of woo-woo, a term I use to describe other semi-scientific sets of beliefs. Lenny introduced to our circle the political ideas of the Marquis de Sade’s via Justine or the Misfortunes of Virtue. Some of us, including myself, also read Justine and other things de Sade wrote, something that helped me in a Theater of Cruelty course I later took as an undergrad at Brooklyn College (Theater of Cruelty, associated with the French artist Antonin Artaud, was a brief movement in experimental theater in the 1930s).

Lenny was also the first to pick up on Allen Ginsberg. The goings-on of Ginsberg and the remaining Beats were always news in the Village Voice, and reading the weekly Village Voice was essential to all of us. The Beats was a shorthand term for the Beat Generation, a group that coalesced in the early 1950s primarily in San Francisco and New York City’s Greenwich Village who elected to be alienated from conventional society, eschewed consumerism, and found release from the post-WW II constraints of American society via illumination (or spirituality) through poetry, jazz, drugs, sex (free and otherwise), literary aspirations, and Eastern religions. Collectively known and derided as Beatniks (a term derived from Beat and Sputnik – Sputnik was the first satellite launched by the Soviet Union in 1957, an event that woke up America to the USSR’s technological savvy), Beatniks were represented by the Maynard G. Krebs character (portrayed by Bob Denver … yes, THAT Bob Denver) in the TV show, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis that ran on CBS from 1959 – 1963, and in reruns in perpetuity. Sweatshirt-wearing, bongo-playing, and goateed Maynard G. Krebs was fond of saying, “What? Me Work?” and this catchphrase pretty much summed up the Beats for many Americans.

Lenny would bring down his copy of Howl and Other Poems and read it to us as if he, Lenny, were Allen Ginsberg, which of course was preposterous. And hilarious. There are a few sections of Howl filled with erotic love focusing on body parts and things we all knew happened but were far away from our world, and we thought Ginsberg’s descriptions were hilarious, too. Lenny and our other resident intellectual got what Ginsberg was all about, but the rest of us, myself included, thought of Ginsberg as a character. But our world was only a dozen or so years from Howl’s publication in 1955 and only later on, much later on, did I realize that Howl was a poetic autobiography of Ginsberg’s. More important to me was Ginsberg’s poem, Kaddish, published in 1961 in Ginsberg’s Kaddish and Other Poems. Kaddish was a remembrance of his mother Naomi, who died on June 9, 1956. And Kaddish I listened to on this 1959 Fantasy label recording today.

Y’hei sh’mei raba m’varach l’alam u-l’almei almaya.

In the mid-1960s I had no idea that later on in my life I would be taught an important life lesson by Allen Ginsberg. Personally.

In Spring 1990 I traveled to Eastern Europe with a friend to see what the effect of the fall of the Berlin Wall had on Germany, and after seeing Berlin, East and West, we took a train to Prague and then Budapest. We found ourselves in Prague on May Day, May 1, a holiday celebrating Spring and International Worker’s Day, a real public holiday. My friend and I were at Prague’s Old Town Hall to see a marvelous astronomical clock, The Prague Orloj, built in the fifteenth century. The public space around the clock was festive with outdoor cafes serving coffee, beer, and all different types of food. In the large public square adjacent to where we were was a festival going on with a large crowd responding to public speakers, all of whom were speaking in Czech.

That is, until I hear a familiar voice telling the crowd, in English, how proud he was to be made Kral Majales, the King of May Day this year (1990) in Prague (in 1965, Prague student activists named Ginsberg Kral Majales, and Ginsberg was deported soon thereafter).

But in 1990 Prague was free, and it didn’t take me long to realize that the voice speaking was that of Allen Ginsberg. At the time Ginsberg was a Distinguished Professor of English at Brooklyn College, my alma mater, where I got my B.A. and M.S., and where I had taught as an adjunct in the Department of TV and Radio from 1975 onwards. I had something in common with Allen Ginsberg! Brooklyn College. Teachers. Hoo-hah!

Yitbarach v’yishtabah, v’yitpa’ar v’yitromam, v’yitnasei v’yit-hadar, v’yit’aleh v’yit’halal sh’mei d’kudsha, b’rich hu, l’ela min kol birchata v’shirata, tushb’hata v’nehemata, da-amiran b’alma, v’imru amen.

So my friend and I angled our way through the crowd and positioned ourselves at the steps to the stage, where I figured out Ginsberg would make his exit. And soon he did. I prepared what I wanted to say to this esteemed poet, intellectual, public figure, and a man who represented New York City much like Walt Whitman did more than a century earlier. Most important to me, Ginsberg was a fellow worker within the City University of New York. And this was International Worker’s Day. We were almost like friends.

As Ginsberg walked down the wooden staircase from the stage to the plaza, I extended my hand and grabbed Ginsberg’s. I said something to the effect of, “Allen, you’re a Distinguished Professor at Brooklyn College and I went to Brooklyn College and teach there too. And we’re both here in Prague on May Day!”

Ginsberg shook my hand, looked right through me and said, “That’s great.” And then walked on.

Y’hei sh’lama raba min sh’maya, v’hayim, aleinu v’al koi yisrael, v’imru amen.

Initially I thought I had been slighted, but I soon realized what a valuable lesson I learned, and from Allen Ginsberg, himself. Since that day, May 1, 1990, whenever someone says something to me that is important to them yet has little or no consequence to me, I look the person straight in the eye, shake their hand, and say, “That’s great.” You can’t imagine how often I find myself saying, “That’s great” to others. And I’m going to predict, right here and now, that you will too. Tell ‘em Allen Ginsberg inspired you.

So at this point, for my brother, Lenny, I’d like to finish the Mourner’s Kaddish, even though I should wait until November. But I’m a rebel, just like Allen Ginsberg.

Oseh shalom bi-m’romav, hu ya’aseh shalom aleinu v’al kol yisrael, v’imru amen.

Mourner’s Kaddish in English

Exalted and hallowed be His great Name. (Congregation responds: AMEN)

Throughout the world which He has created according to His Will. May He establish His kingship, bring forth His redemption and hasten the coming of His Moshiach. (Cong: AMEN)

In your lifetime and in your days and in the lifetime of the entire House of Israel, speedily and soon, and say, Amen.

(Cong: “Amen. May His great Name be blessed forever and to all eternity, blessed.”)

May His great Name be blessed forever and to all eternity. Blessed and praised, glorified, exalted and extolled, honored, adored and lauded be the Name of the Holy One, blessed be He.

Beyond all the blessings, hymns, praises and consolations that are uttered in the world; and say, Amen. (Cong: AMEN.)

May there be abundant peace from heaven, and a good life for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen. (Cong: AMEN.)

He Who makes peace in His heavens, may He make peace for us and for all Israel; and say, Amen. (Cong: AMEN.)