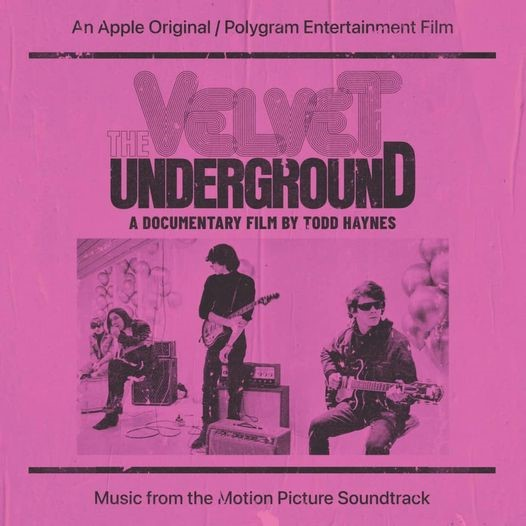

The Velvet Underground documentary directed by Todd Haynes.

Brian Eno is reported to have said that the first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band. I love VU, but I always thought that we would have all been better off if everyone who bought the first Velvets album instead opened up a same-day dry cleaners.

Sara and I saw the Todd Haynes documentary film, The Velvet Underground at the Westport (Connecticut) Public Library on Friday, October 15. Todd Haynes was a perfect choice to produce and direct this film, because the band, the era (the 1960s) the location (New York City), the link to fame (Andy Warhol), and the mise en scene of much of the action (Andy Warhol’s Factory and its rotating cast of characters) are all up Haynes’ alley, which is to say an alley consisting of the careers of rock musicians and those folks who love and sometimes exploit them.

This documentary premiered at the Cannes Film Festival earlier this year, where the far more interesting Leos Carax film, Annette, with music by Sparks also premiered, but that’s another story. Both films are difficult films to enjoy without a knowledge of the music of The Velvet Underground for its namesake documentary, and the music of Sparks for Annette. I happen to like both films and both bands.

As a New York City teen in the 1960s, my friends and I followed the work of Andy Warhol as reported in The Village Voice and sort of understood the notion of pop art, but what we clearly saw was that the comings and goings of most of the folks who made up Warhol’s Factory dramatis personae were good looking, limelight seeking, self obsessing, overly theatrical individuals who, like NY Senator Chuck Schumer, never met a camera that wouldn’t work better if focused on him. Or in the case of many of the Factory folks, her. And that’s what Warhol did: focus his camera on good looking, limelight seeking, self obsessing, overly theatrical types. I looked at his part of The Factory as if it were the flip-side of Camelot. Both, by the way, were near meaningless media shortcut-constructions.

Perhaps I’m being too harsh.

And perhaps not.

As for the history of the band, John Cale and Maureen (Mo) Tucker offer their recollections in this documentary, as do others, including Jonathan Richman (an early VU acolyte whose description of the Velvets’ music was the clearest of all the folks who attempted to describe what they attempted to do), and Amy Taubin, a film critic who was there at Warhol’s Factory to see the relationship between Warhol and the Velvets at its inception. It looks to me like Warhol used Lou Reed and John Cale, and Lou Reed and John Cale used Warhol to gain some traction in the music world at the time. Cale offers a history of minimalism as his entrance point to the Velvets, and as a result of discourse we meet Karlheinz Stockhausen and La Monte Young, early adopters and creators of electronic music and minimalist music, respectively. Cale makes the case that minimalism was what VU (that is, Reed and Cale) had in mind at the band’s beginning, and God knows minimalism and noise were both part of the band’s first two albums (The Velvet Underground & Nico and White Light/White Heat), as well as part of the attraction of both recordings. By the way, both of these albums were released initially on the Verve label, and I clearly recall how awful sounding these albums were. This had nothing to do with the Velvets, and all to do with the actual recordings and disc pressings. Verve’s parent company at the time, MGM Records, was not well known for high quality recordings, even though at the time, MGM was a major label.

Perhaps I’m being too harsh again.

And again, perhaps not.

The film then focuses on the creative and personal animosity between Reed and Cale, which appeared to be the result of Reed’s interest in moving the band in a more musical – and less experimental – direction. Beginning with the band’s third album, and with Reed’s firing of Cale and the addition of bassist Doug Yule, the band did begin to move in a more musical direction. As you likely know, Cale has had a long and prodigious musical career following his departure from the Velvets, as did Reed after he broke up the band. But by the third album, The Velvet Underground was clearly Lou Reed’s baby.

Little is said about Loaded, the fourth and final album of the band. To me this is disappointing because I have always held it to be the band’s best, though most other original VU fans disagree … if they’re still alive. Loaded’s sales were disappointing, and from a band whose sales during their initial run were always disappointing, this is saying something. I possess a promo copy of Loaded, one that I purchased soon after the album’s release at a Brooklyn-based used record store, Titus Oaks. Many years later, while working as a recording engineer, I had the opportunity to meet Lou Reed while he was a guest on a satellite-delivered radio talk show. I brought in my promotional copy of Loaded for Reed to sign. Reed looked at the album, and pointing to the big “FOR PROMOTIONAL USE ONLY” sticker on the album cover, looked at me and said, “This is why we didn’t make any money.” Funny guy, that Lou.

As a film, this is one impressive look at The Velvet Underground in its NYC-centered social setting. As an item of historical interest, it may only attract the attention of those who have heard of The Velvet Undeground, as well as Lou Reed and John Cale fans. The musings of VU drummer Mo Tucker were a bonus. If anyone’s feet were firmly planted on this earth during and after VU’s run, it’s Mo’s. But the musings of film critic Amy Taubin left a larger mark on me. Taubin, in her description of the environment of Warhol’s factory, pointed to the toxic atmosphere of the Factory for its hangers-on, with many of such on-hangers imagined as an entrance to a glamorous lifestyle, and were oblivious to the inevitable outcome of their hanging.

I’m also reminded of recent Facebook criticisms in The Wall Street Journal, and Connecticut Senator Richard Blumenthal’s Congressional hearing earlier this month, and in particular, the testimony of Facebook critic Frances Haugen at Blumenthal’s hearing. Facebook, and in particular Instagram, argued Haugen, negatively affect millions. Adults should know better, but teens may not. But this is clear … if you live in a toxic environment, you increase the likelihood of disease. In the case of Warhol’s Factory, it appears that only adults were affected, thank God. And this is not a case of imposing 2021 standards on to 1965. This 1965 toxicity was pawned off as edgy artistry blending with large-scale cultural change. It was BS at the time, and it remains BS today.