Sometimes a Temporary Job Leaves a Lasting Impression.

Hacking has a different meaning today than when I hacked for a living.

It was 1973. I had graduated from Brooklyn College in January, and left a job I had at an audiotape distributor in May. Having a job and earning money was always important to me. In June, I began a job as a teacher at a downtown Brooklyn private remedial school, a place where Brooklyn elementary school kids would be sent to by their parents to 1. learn material the kids hadn’t learned during the school year, and 2. avoid being left back in the Fall.

Incoming kids were evaluated by school staffers and were given grade-appropriate workbooks to handle. My job was to roam around the classroom to help and guide the students through this remedial work. I liked the job, but the kids didn’t like being there. They’d rather be free during the summer. The job paid $4.00 per hour, twenty hours per week. $80.00 gross weekly. Not a lot of money even in 1973.

Sadly, this wasn’t enough to keep me going. Soon after I started teaching I figured I needed about $110.00 incoming per week to afford my rent, food, and transportation until I began a graduate program at Brooklyn College in the Fall, a program where I would be paid to be an Intern in the Department of TV and Radio through the academic year. In return I would serve as a teaching assistant in lecture hall classes and TV production courses at Brooklyn College’s TV facility.

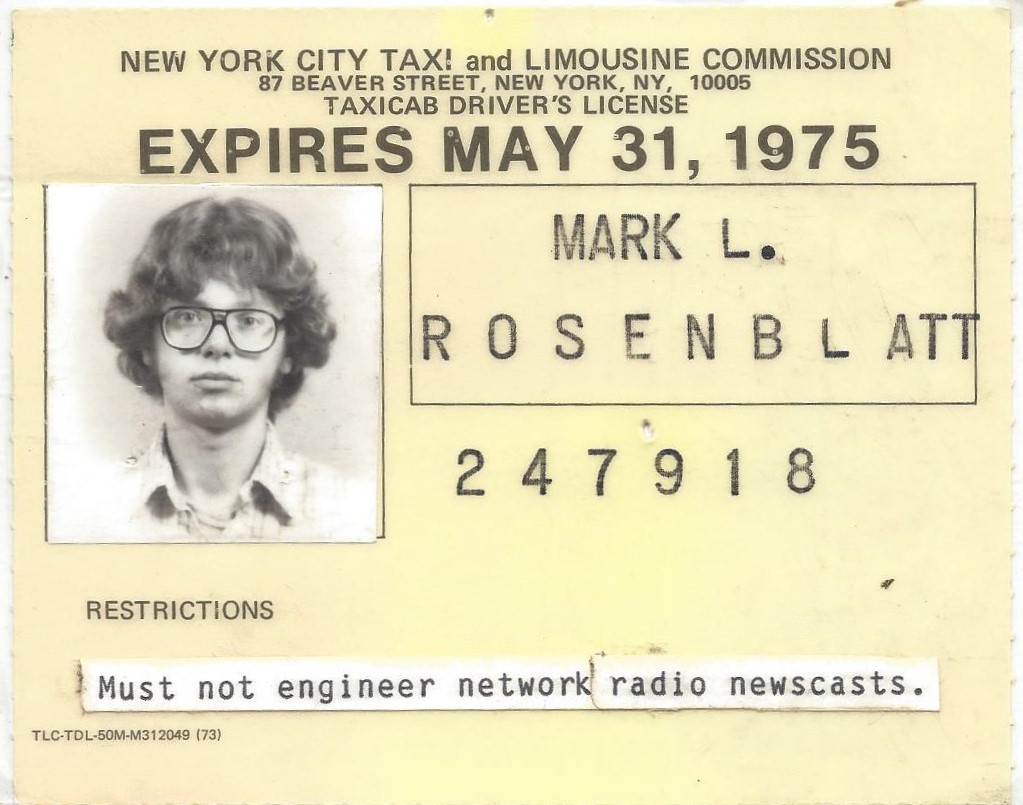

So I made a decision. I needed money. I got my hack license to drive a NYC yellow cab during the Summer of 1973 and quit my teaching job. Today that would be called a reverse job path. In 1973 it was called common sense. In fact, many of my older friends drove cabs while in school, and both of my younger brothers, Len and Philip, both now gone, drove at one time or another after I did.

It wasn’t a great job, there was an element of danger (you might get robbed, or worse), and you’d never get rich, but I liked driving, I liked driving in Manhattan, and I earned enough money to keep me going until I began grad school at Brooklyn College in September 1973.

I was able to clear roughly $125.00 weekly from driving an afternoon to midnight shift three weekdays, usually Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, and early morning shifts on weekends. I’d head into Manhattan from the Love Taxi garage in Bensonhurst, Brooklyn and tried to stay in Manhattan as much as possible. On weekdays, business depended on the action in the city and Friday was usually good no matter what. Weekends were dead until 11:00am, and until 11:00am is when I spent time driving around and through Central Park, when such driving was permitted, and driving in and around the area of Gracie Mansion. On weeknights, if I made my money – I earned 39% of my bookings plus tips – I would head down to Chinatown or to one of the remaining automats, buy the early NY Times, and kill time until I had to bring the cab back to the garage at roughly midnight. Once I made my money for the night (or day) I was done. No reason to court danger.

I got into two minor scrapes while driving, something unavoidable if you’re going to drive in Manhattan forty hours per week. The dispatcher gave me some good advice. “Accidents happen,” he told me, “but don’t get into an accidents in intersections.” Doing so meant that you either jumped a red light or tried to make it through a light turning red.

The worst thing that happened to me was when one fare threw up in my cab and I had to clean up the mess. The Love Taxis were 1972 and 1973 Dodge Coronets. When I got one of the new 1973 Coronets, I was in heaven. Not air-conditioned heaven – that was years off – but I got to drive in a tight car that still had some of that new car smell.

On my first few days out I had this fractured fairy-tale idea of some woman fare deciding to take me home with her, but the only action I saw was on three separate occasions when guy fares tried to pick me up. The first time I said, “No.” The second time I said, “Look, guy, I’m working.” But the third time it happened I decided to use diplomacy and have some fun. “Thank you for the offer, and I’m really touched, but I’ve got another few hours to go before I have to bring this baby back to Brooklyn.” And you know what? I got approximately the same percentage-of-the-fare tip from all three guys. NYC is tough.

After an eight-hour shift, I would take a bus from the Love Taxi garage in Bensonhurst to where I lived on St. Paul’s Place near the Parade Grounds in the Flatbush section of Brooklyn. The bus dropped me off at the Church Avenue subway stop roughly two short blocks from an apartment I shared with my college friend, Mark Solomon. Shared that is until he departed for a Ph.D. program in Clinical Psychology at the University of Cincinnati. To this day, say “Ohio” to Solomon and he still twitches, the result of his lengthy stay in Cincinnati. If you mention St. Paul’s Place, he denies ever living there.

Across the street from the bus stop where I got off was Duggan’s Bar, a typical NYC neighborhood Irish bar, and one that is long gone. In 1973 there were two types of bars in NYC: upscale and neighborhood. The beer utopia we’re living in today was fifty-plus years off, and where I lived was anything but upscale. It was more no scale. And Duggan’s was a simple neighborhood bar. Fairly clean, with no heads-on-bar patrons at midnight. I was not really a drinker, but I felt that hey! I’m a working man. And if I want a beer after work, I’m going to get me a beer! But as a longhair non-Irish college student patron, I knew others might take exception to my view of myself. So wearing my cabbie hat (to suggest that I’m either a working cabbie or an old retired newsboy), I sat down at the bar, and I sort of felt that all bar chatter stopped. It likely didn’t, but that’s what I felt. The bartender came over, asked me what I wanted, poured a beer for me while I looked straight ahead to avoid eye contact with other patrons – all while Duggan’s chatter returned to normal. No one spoke to me, which I interpreted as a good thing.

What gave me the inspiration to walk into Duggan’s and sit at the bar at midnight dates back to the summer of 1970. That summer I started hitchhiking along the Belt Parkway to get to work (at the audio distributor I mentioned earlier, Fine Tone Audio) from my parent’s apartment in Howard Beach, Queens to the Ocean Parkway exit in Brooklyn. What I quickly learned is that if you appear at the same place at the same time day after day, you are quickly perceived to other passersby, and in this case, drivers, as part of the scenery and consequently no threat. I found it was fairly easy to get picked up for the fifteen-minute ride to work, and after two weeks I had regulars picking me up. By regulars I mean folks who knew me by name and I theirs. Being able to hold a conversation with anyone short of a murderer is a plus in hitchhiking. An umbrella for rainy days helps too. No one wants a soaking wet hitchhiker.

Armed with this knowledge of showing up at the same place at the same time day after day makes you part of the scenery, I returned to Duggan’s the following night, took the same exact open bar stool, and noticed the same guy sitting to my right. Bar chatter didn’t diminish, and the bartender came over and got me a beer. The guy to my right then turns to me and says something like, “How you doing?” and I was off to the races, where off to the races means I no longer felt like I could get killed at any moment. Sure, I could still get killed, but not here. Not that night, anyway. As Brother Theodore would say, “In death, there is hope.”

I’ve seen that part-of-the-scenery perspective play out many times in the past 50-plus years, and I’ve always used it to my advantage. Never recklessly, though.

After I stopped driving I always thought, “No matter what happened in my life, I could always drive a cab.” I still think that way today. If my younger brothers were still around, they might think the same way. And I still have my hack license.

I drove a Yellow Cab for IkeStan during my Brooklyn College days and loved it. The great (crazy) fares and requests made it a very enjoyable experience. I never knew what the day would bring which was part of the allure.

Love the restriction on your license!

!!!