Woodstock Recalled.

Every year at this time, Woodstock is in the news. So is war, somewhere, and intolerance, everywhere, but what can you do? Sure, Woodstock, the 1969 music festival, is usually portrayed as the defining event of an era that blended youthful hope, a recreational drug culture, anti- (Vietnam) war sentiment, and later on, the full flowering of baby boomers, and the men and women who loved them.

Yeah, yeah.

In early 2016, a Texas high school teacher contacted a longstanding friend of mine (and one since seventh grade!), who also attended Woodstock. This teacher was preparing a primary-source exercise in her eleventh-grade high school History class, and after my friend volunteered me as a primary source, this Texas high school teacher submitted to me, and others, a series of questions about our Woodstock experiences.

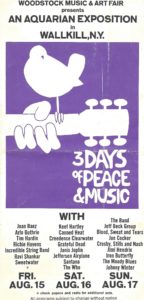

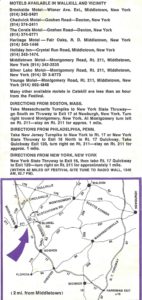

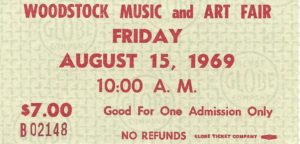

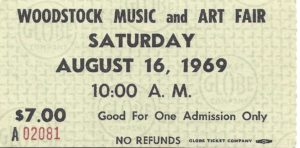

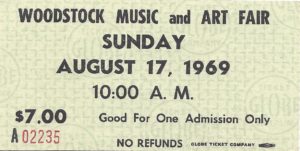

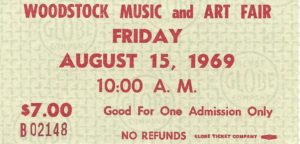

What follows are my answers to the teacher’s series of questions, which were constructed – according to the teacher – by students in her class. As background, I was 18 at the time of Woodstock, three semesters into my undergraduate degree at Brooklyn College, living at home in Howard Beach, Queens with my parents and two younger brothers, both of whom are now deceased, working part-time at a variety store during the school year and full-time during the summer of 1969. I went to the festival with two friends, ages 18 and 19, and had visited the Bethel site two weeks earlier with these same two friends, and determined that no festival of 50,000 people (the advertised attendance before the event) could take place in two weeks’ time at the Bethel location. All that was up two weeks before Woodstock began was the frame of the main stage at the bottom of a gentle sloping hill. Two weeks earlier we had driven up to the original site in Wallkill, NY where Woodstock was initially set to take place (see my original brochure at the end of this piece, along with images of my tickets, which I still possess). At that time, too, we determined that the festival could not be put together in four weeks.

What did we know?

The questions posed to me by the Texas high school teacher and her students are clearly seen in my responses, below. The numbers reflect the questions. These are high school students, after all.

On Woodstock

1. My friends and I first heard about Woodstock on NYC-based rock radio stations and in advertisements in a NYC-based weekly newspaper, The Village Voice, that focused on art, culture and politics. Initially, Woodstock was to be a two-day event, and two friends and I purchased tickets by mail for the event. After we got tickets, a third day was announced, and we then bought tickets for the third day, again by mail. I recall arguing on the phone with Woodstock ticket-sellers that because my friends and I purchased discounted tickets for the two-day event, we should be entitled to the new discount price for the three-day event instead of purchasing the new third-day ticket at full price.

We got the discount. Hoo hah!

2. I was 18 at the time, and living at home in Howard Beach, Queens, in NYC. My parents thought going to such an event was not the smartest decision I ever made, but at 18, I had been in college for a year and a half, and was working part-time during the school year and full-time during the summer, and could make such decisions on my own. My Dad ended up lending me his car for the 2.5 hour drive from NYC to Bethel, NY for Woodstock.

3. Woodstock was advertised as a musical event – a three-day outdoor concert, or series of concerts. My friends and I saw the “three days of peace and music” part as meaningless advertising. Attendance projections by the Woodstock promoters gave us the impression that 50,000 people would attend, the same size crowd that could be expected at Yankee Stadium during pennant races. 50,000 people? No big deal.

4. I drove with my two friends in my Dad’s 1966 4-door Oldsmobile Dynamic 88, a tank of car with a 425 cubic inch monster engine. I left at midnight on Friday morning because my friends and I knew there would be traffic, and while the concert was to begin Friday evening, we wanted to be at the event early enough to wander around and take in the sights, whatever they would be. It took about two hours to drive there, and six more hours inching along local roads before we were able to get into a parking lot, which turned out to be a muddy field. My younger brother, who was 17 at the time, and a friend of his left some 6 hours after I did, and was not able to get anywhere near the event, and ended up driving home the same day, and before the concert began.

5. When my friends and I got to the event – at something like 8:30am Friday morning, and some 11 hours before the first act was scheduled to go on – we saw that the promises made by Woodstock organizers of food being sold (we brought little of our own because we were promised we could buy food at the event), that some semblance of order was to be maintained (no tickets were collected because, well, there were no ticket-takers to collect such tickets and protective fences were already knocked down), and facilities to be provided in the form of Porta-Potty six-packs (too few for the crowds we saw) could not handle the crowds we spotted, but hey! This looked like it could be fun.

6. Woodstock, in my opinion, did not rise to the level of experience, so I couldn’t tell you what the Woodstock experience was like. My friends and I looked around, and we immediately saw that we were much younger than the average attendees, who I would put in the area of 25, and while my friends and I dressed like our contemporaries, we were all college students and part-time workers, and NOT hippies, or hippie-wannabees. Sure, we wanted to meet girls like everyone else, but we would often parody others who would use “Hey, mannnnnnn …” as an introduction to every sentence. Sure, to get high was OK and fun, but was NOT a full-time occupation because it was then, and still remains, a dead end. I thought at the time, and still do to this day, that most of those who argue for lives outside of contemporary culture do so poorly. Some can make a good case, but most are … well … doomed.

7. The primary reason that my friends and I went to Woodstock was to see bands and artists all at the same time over three days in one place. Some of the artists my friends and I had already seen. We lived in New York City, and all bands eventually came to the city, although you couldn’t always get tickets or afford to see all the bands you wanted to see. So this was an opportunity to see a lot of big name bands at an outdoor location, but I also knew that many of the bands were dreadful, and we would have to sit through such bands as well. That’s called realism. Popular music, and especially rock music, was the motivating reason for my going to Woodstock. I spent much of my free time listening to music, talking about bands, and making friends with like-minded people.

8. I was a big fan at the time of Richie Havens and Tim Hardin, had seen both in small clubs in NYC before Woodstock, and looked forward to seeing them again – on the first night, Friday evening. Other bands I liked played on the second and third nights, but by then I was long outtathere (see my next response, below).

9. and 10. I didn’t WISH I could be back home. I WENT home. One of my friends and I took hallucinogens when the music started on Friday evening. It was the first time either of us had done so, and the experience was a little bit overwhelming, and a little too overwhelming for my friend, who clearly was not doing too well. And then it started to rain on the first night about two hours into the show. I don’t know about you, but I always felt that a key mark of human intelligence was whether a person knew enough to get out of the rain. And especially so in an open field. And even more especially so if there was a chance of lightning. And still even more so if your friend was having a really bad experience and you (yourself) could imagine things turning really bad really quickly. So in the rain, my friend and I started to wander back to my parked car to get out of the rain. We had long since lost track of our third friend, who elected NOT to take the hallucinogen we did. After about an hour, we found my car in a field of mud, and got inside. After a few minutes, our third friend knocked on the car’s window, and he got inside as well. While we had planned to sleep in my father’s large car, we hadn’t planned to do so soaking wet. Or muddy.

The next morning, the rain had stopped, and it was partly sunny outside. I was feeling sick due to the after-effects of the hallucinogen, as did my friend. All three of us were greasy. I opened the car door to step outside, and stepped into roughly six inches of mud. My friends and I all got out of the car and began a search for food to purchase (although we did have snack foods in the car). Not surprisingly, there was no food to be found anywhere, and the lines for Porta-Potties were endless. Playing over the Woodstock PA system — over and over and over again — was Suite: Judy Blue Eyes from the first Crosby, Stills and Nash album, which was released less than three months earlier, and every time the song came to “I am yours, You are mine, You are what you are, You make it har-ar-ar-ar-ard,” I wanted to puke, and to this day I can’t listen to that song, and pretty much all of C, S and N. After an hour of this, we quickly asked each other, “What should we do?” To a man, we agreed. “Let’s get the hell out of here!” And we did. It was only then did we realize, and only generally, what was happening. So many people attempted to get to Woodstock that the northbound side of the New York State Thruway (Interstate 87 northbound) was STILL shut down the day after Woodstock started. This was OK with us, because we were headed in the OPPOSITE direction – southbound on Interstate 87 back to NYC. Somehow we managed to get my car out of the muddy field and back onto local roads headed AWAY from Woodstock. And this is where my favorite Woodstock memory took place.

Once on the highway, my friends and I agreed to stop at a highway rest area to get something to eat and to fill up my Dad’s car with gas. At the first opportunity, we stopped at a Hot Shoppe, one of a chain of franchised-by-New York State highway restaurants. In 1969, the highway rest stops of today – food courts with multiple franchises – could not even be imagined! The idea of a food court to a 1969-era smart-ass college student (me!) would’ve likely conjured up images of judges and juries determining whether ketchup-on-hot-dog-loving customers could be sentenced for their clearly aberrant eating behavior! No such thing as a food court existed in 1969, and certainly NOT on the New York State Thruway. We lucky New Yorkers had Hot Shoppes, which were part cafeteria, part restaurant. They were awful, but we didn’t care. The three of us looked like hell, with mud on our jeans, hair slicked down, and in general, grunge-y, some twenty years before grunge came into fashion. But we were hungry. And soon after we entered, some kid got a look at us, and then yelled out to her mother, “Look, Mom, hippies!” And while we knew that the kid was pointing to us, the three of us turned around, and shouted out, “Hippies? Where? What do they look like?” And then bent over laughing. Such was life back then.

So for the time being we ate, filled my Dad’s monster Olds with gas and then drove the 2 hours or so back to NYC. While driving we listened to NYC rock radio and top-of-the-hour radio newscasts describing the events at Woodstock while or soon after they took place – as news stories. Highway drivers like us and millions of others were being fed information about an event that was pretty much out of control, though to the credit of the festival’s attendees, was by and large peaceful. Over the next few days we read about Jimi Hendrix and his version of the Star-Spangled banner. We also saw how press coverage directed people to view Woodstock as a magical experience instead of a poorly-run three-day concert. When you can make mud sound like magic, either you’re a good storyteller or your audience desperately wants to believe mud IS magic.

11. I really think that Woodstock is a case in point example of media exaggeration of newsworthy social events and simplifying the meaning of such events – because while truth may be stranger than fiction, fiction’s a hell of a lot easier to package to sell stuff.

12. Yes, I had actively protested against the U.S. War in Vietnam. Some wars are sadly necessary. But the war in Vietnam made no sense to me. And it’s important to note that such protests had only the remotest link to Woodstock.

13. The one final thing I’d like to say about Woodstock is that as an historical reference point, its meaning is blown way out of proportion to me, anyway.